Introduction: Understanding Measles

Measles, also known as rubeola, is a highly contagious viral disease that primarily affects children but can strike individuals of any age who lack immunity. Caused by the measles virus—a member of the Paramyxoviridae family—the infection spreads through respiratory droplets when an infected person coughs or sneezes. Its rapid transmission and classic clinical picture have made measles a focal point of public‑health discussions for centuries.

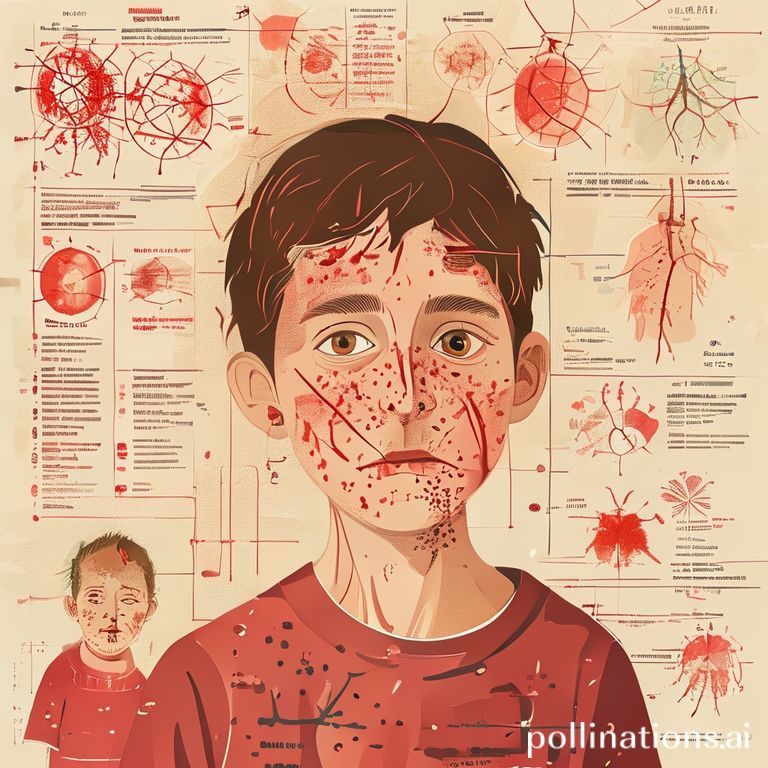

The hallmark signs of measles begin with a prodrome of high fever, cough, runny nose, and watery eyes (conjunctivitis). Within a few days, a distinctive red, maculopapular rash emerges, typically starting at the hairline and spreading downward over the face, neck, trunk, and limbs. A small white spot with a bluish-white center, known as Koplik’s spots, often appears inside the mouth before the rash, serving as an early diagnostic clue.

Understanding the disease’s impact requires a look at its potential complications, which can be severe and life‑threatening:

- Bronchitis and pneumonia – the most common cause of measles‑related deaths.

- Encephalitis – inflammation of the brain that can lead to long‑term neurological damage.

- Acute otitis media – middle‑ear infection that may cause hearing loss.

- Severe diarrhea, which can lead to dehydration, especially in malnourished children.

Globally, measles remains a leading cause of vaccine‑preventable childhood mortality. Before widespread immunization, major epidemics occurred every few years, claiming millions of lives. The introduction of the measles‑containing vaccine (MCV) in the 1960s dramatically reduced incidence, but outbreaks still flare up in regions with low vaccination coverage or where vaccine hesitancy undermines herd immunity. The World Health Organization estimates that over 140,000 deaths still occur annually, most of them in low‑income countries.

Because the virus can remain airborne for up to two hours in an enclosed space, even brief exposure in crowded settings—schools, hospitals, public transport—can spark an outbreak. This underscores the critical importance of maintaining high immunization rates (≥95% for two doses) to protect both individuals and communities. In the sections that follow, we will explore the virology of measles, detailed symptomatology, prevention strategies, and the latest advancements in outbreak control.

Causes and Transmission

Measles, also known as rubeola, is an acute viral infection caused by the measles virus—a single‑stranded, enveloped RNA virus belonging to the Paramyxoviridae family. The virus is highly contagious; a single infected individual can release up to 10,000 infectious particles into the air with each cough or sneeze. Because the virus resides in the respiratory secretions, it spreads primarily through aerosolized droplets and, to a lesser extent, via direct contact with contaminated surfaces.

Understanding how measles moves from person to person is crucial for effective public‑health interventions. The virus can remain viable in the environment for up to two hours, allowing it to travel over distances of several meters in enclosed spaces. This airborne capability explains why measles outbreaks often occur rapidly in schools, daycares, and other crowded venues where individuals share close proximity for extended periods.

- Respiratory droplets: When an infected person coughs, sneezes, or even talks, they expel droplets that contain the virus. These droplets can be inhaled by anyone nearby, making the immediate vicinity the highest‑risk zone.

- Aerosol transmission: Smaller particles can stay suspended in the air, traveling farther than the typical 1‑meter “droplet” distance. In poorly ventilated rooms, these aerosols can accumulate, increasing the risk for everyone in the space.

- Fomite transmission: Although less common, touching objects (doorknobs, toys, handrails) contaminated with respiratory secretions and then touching the mouth, nose, or eyes can introduce the virus.

- Vertical transmission: Rarely, measles can be transmitted from a pregnant woman to her fetus, leading to serious complications for both mother and child.

Several factors amplify the spread of measles:

- Low vaccination coverage: Communities with <90% or lower measles‑containing vaccine (MCV) uptake are especially vulnerable to outbreaks.

- High population density: Urban centers and refugee camps provide ideal conditions for rapid virus propagation.

- Seasonal variation: Measles incidence often peaks during late winter and early spring, coinciding with increased indoor crowding.

Because the virus suppresses the immune system early in infection, individuals become infectious before the classic “Koplik spots” appear and remain so for about four days after the rash emerges. This pre‑rash contagious period makes early detection and isolation challenging, emphasizing the importance of vigilant surveillance, timely vaccination, and robust infection‑control practices.

Symptoms, Stages, and Complications

Measles (rubeola) is a highly contagious viral illness that follows a fairly predictable clinical course, but its manifestations can vary widely depending on the host’s age, immune status, and access to timely medical care. Understanding the hallmark signs, the sequential stages of the disease, and the potential complications is essential for early detection, prompt isolation, and appropriate treatment. Below is a comprehensive overview that breaks down each component in clear, digestible terms.

Typical Symptoms

- Fever: Often the first symptom, rapidly climbing to 104°F (40°C) or higher.

- Prodromal cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis: Known as the “three C’s,” they give the illness its classic “cold‑like” beginning.

- Koplik spots: Tiny white or bluish lesions on the buccal mucosa, usually appearing 2–3 days before the rash and considered pathognomonic.

- Maculopapular rash: Begins at the hairline and behind the ears, spreading downward to the trunk, arms, and legs over several days.

- Generalized malaise: Fatigue, loss of appetite, and irritability are common, particularly in children.

Stages of the Disease

- Incubation (10–14 days): The virus replicates silently; no symptoms are evident.

- Prodromal stage (2–4 days): Fever spikes, and the three C’s appear; Koplik spots may emerge.

- Rash stage (3–5 days): The characteristic red blotchy rash becomes visible and spreads cephalocaudally. Fever may persist but often begins to subside.

- Recovery phase (7–10 days): The rash fades, skin peels, and the patient gradually returns to baseline health, provided no serious complications develop.

Potential Complications

While many patients recover without incident, measles can lead to life‑threatening complications, especially in infants, adults, pregnant women, and immunocompromised individuals. Key complications include:

- Pneumonia: The most common cause of measles‑related death; can be viral or bacterial.

- Encephalitis: Inflammation of the brain that may cause seizures, permanent neurological deficits, or death.

- Acute otitis media: Middle‑ear infection that can result in hearing loss if untreated.

- Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE): A rare, progressive neurodegenerative disease that can appear years after the initial infection.

- Diarrhea and severe dehydration: Particularly dangerous for young children in low‑resource settings.

- Pregnancy complications: Increased risk of miscarriage, preterm labor, and low‑birth‑weight infants.

Recognizing the symptom progression and being aware of the potential complications empowers caregivers, clinicians, and public‑health officials to intervene quickly, isolate cases, and mitigate the spread of this vaccine‑preventable disease.

Diagnosis and Treatment Options

Measles, caused by the highly contagious measles virus (Rubeola), presents a classic set of clinical signs that allow physicians to make a prompt diagnosis. Early recognition is essential not only for initiating appropriate care but also for preventing further spread within the community. The diagnostic process typically begins with a thorough medical history and physical examination, focusing on the hallmark features of the illness.

Key clinical clues include:

- Koplik spots: Tiny, white‑to‑bluish lesions with a reddish halo that appear on the buccal mucosa 1–2 days before the rash.

- Cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis: The “three C’s” commonly precede the rash and signal the onset of infection.

- Maculopapular rash: A red, blotchy rash that typically starts on the face and spreads downward to the trunk, arms, and legs over several days.

If the clinical picture is ambiguous, laboratory confirmation becomes important. The most reliable tests are:

- Serology: Detection of measles‑specific IgM antibodies in serum, which usually become positive within 3–5 days of rash onset.

- Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT‑PCR): Identification of viral RNA from throat swabs, nasopharyngeal samples, or urine. This method is highly sensitive and can confirm infection even before antibodies are detectable.

- Viral culture: Rarely used in routine practice due to the need for specialized facilities, but valuable for epidemiological investigations.

Treatment Options

Unlike many bacterial infections, measles has no specific antiviral cure; management focuses on supportive care and preventing complications. Core treatment strategies include:

- Vitamin A supplementation: The World Health Organization recommends two doses of 200,000 IU (or age‑adjusted equivalents) given 24 hours apart for all children diagnosed with measles. Vitamin A has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality, especially in low‑resource settings.

- Hydration and nutrition: Maintaining adequate fluid intake and a balanced diet helps mitigate fever‑induced dehydration and supports immune function.

- Fever control: Antipyretics such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen can be used to lower temperature and relieve discomfort.

- Management of complications: Prompt treatment of secondary bacterial pneumonia with appropriate antibiotics, antiviral therapy for severe immunocompromised cases (e.g., ribavirin), and careful monitoring for encephalitis or otitis media.

- Isolation precautions: Infected individuals should remain isolated for at least four days after rash onset to prevent transmission to susceptible contacts.

While these measures alleviate symptoms and lower the risk of severe outcomes, the most effective strategy against measles remains prevention through the measles‑mumps‑rubella (MMR) vaccine. Ensuring high vaccination coverage not only protects individuals but also sustains herd immunity, ultimately reducing the need for diagnostic and therapeutic interventions.

Prevention: Vaccination and Public Health Measures

Measles remains one of the most contagious viral diseases on the planet, but it is also one of the most preventable. The cornerstone of measles control is a robust vaccination program, supported by a suite of public health measures that work together to break transmission chains, protect vulnerable populations, and sustain community immunity.

The measles vaccine is typically administered as part of the combined measles‑mumps‑rubella (MMR) shot. Two doses are recommended for optimal protection: the first dose at 12‑15 months of age and the second dose at 4‑6 years, or earlier if the child is at high risk. This schedule has been shown to confer approximately 97 % efficacy after the second dose, creating a strong barrier against the virus.

- High coverage rates: Achieving at least 95 % vaccination coverage in all age groups is essential for herd immunity, reducing the likelihood of outbreaks even when a few individuals remain unvaccinated.

- Catch‑up campaigns: Targeted immunization drives in schools, workplaces, and community centers help close immunity gaps, especially after periods of low vaccine uptake or in areas affected by conflict.

- Cold‑chain management: Maintaining the proper temperature for vaccine storage and transport preserves potency, ensuring that every dose administered is effective.

- Monitoring and surveillance: Real‑time reporting of suspected cases enables rapid outbreak detection, allowing health authorities to intervene before the virus spreads widely.

- Isolation and quarantine: Promptly isolating confirmed cases and quarantining close contacts limit exposure, especially in densely populated settings such as schools and refugee camps.

- Public education: Clear, culturally sensitive communication about the safety and benefits of vaccination counters misinformation and builds trust within communities.

- Travel advisories: Requiring proof of measles immunity for international travelers helps prevent the importation of the virus into regions where it has been eliminated.

Public health agencies also collaborate across borders to share data, coordinate response strategies, and support vaccination efforts in low‑resource settings. By integrating vaccination with vigilant surveillance, community engagement, and rapid response protocols, we can sustain measles elimination and protect future generations from this preventable disease.

Global Epidemiology and Outbreak History

Measles (rubeola) remains one of the most contagious viral diseases known to humanity, and its epidemiological footprint spans centuries, continents, and diverse health systems. Despite the availability of a safe, two‑dose vaccine that confers lifelong immunity in most recipients, measles continues to cause periodic surges, especially in regions where vaccination coverage dips below the critical threshold of 95 %. Understanding the global patterns of transmission, the historical waves of epidemics, and the socioeconomic factors that drive outbreaks is essential for public‑health planning and for sustaining the gains made by eradication campaigns.

Historically, measles followed a classic “boom‑bust” cycle: a large susceptible population accumulated over years of low transmission, then a single introduction sparked a rapid, widespread outbreak that dramatically reduced the pool of susceptibles. In the pre‑vaccine era, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that measles accounted for 2–3 million deaths each year, primarily among children under five in low‑income countries. Following the introduction of the measles vaccine in the 1960s, global mortality fell by more than 80 % by 2000, and the disease was declared eliminated in the Americas in 2016.

However, the past decade has witnessed a series of setbacks that underscore the fragile nature of measles control:

- 2014–2015: The Philippines and Madagascar – Both countries experienced explosive outbreaks after vaccine hesitancy and supply chain disruptions resulted in coverage dropping below 80 %.

- 2018–2019: Europe’s Resurgence – An unprecedented wave swept through Ukraine, France, Italy, and the United Kingdom, with over 100,000 cases reported across the continent, fueled by misinformation and anti‑vaccination movements.

- 2020–2022: COVID‑19 Pandemic Impact – Routine immunisation services were suspended in many low‑resource settings, leading to a 30 % decline in measles vaccine administration and setting the stage for large post‑pandemic outbreaks.

- 2023: Congo Outbreak – The Democratic Republic of Congo reported over 25,000 measles cases in a single year, the largest single‑country outbreak since 2011, highlighting gaps in health‑system resilience.

Geographically, measles incidence remains highest in Sub‑Saharan Africa and South‑East Asia, where pockets of unvaccinated children coexist with dense, mobile populations. In contrast, high‑income regions such as North America and Western Europe experience sporadic cases that are typically imported and contained through rapid contact‑tracing and post‑exposure prophylaxis.

Key drivers of these varied epidemiological patterns include:

- Vaccine coverage gaps caused by conflict, displacement, or logistical challenges.

- Socio‑cultural resistance to vaccination, often amplified by social media misinformation.

- Weak surveillance systems that delay outbreak detection and response.

- Population movements—refugee flows, urban migration, and international travel—that re‑introduce the virus into previously protected communities.

Looking forward, the WHO’s Measles & Rubella Strategic Framework (2024‑2030) emphasizes the need for integrated surveillance, community‑engaged outreach, and sustained political commitment. Only by addressing the underlying determinants of low coverage and by maintaining high‑quality immunisation programs can the global community hope to achieve the long‑sought goal of measles elimination worldwide.

Common Myths, FAQs, and Misconceptions

Measles is one of the most contagious viral diseases known to humanity, yet it remains shrouded in myths, outdated beliefs, and a steady stream of questions that can hinder effective prevention. In this section we separate fact from fiction, answer the most frequently asked questions, and clarify common misconceptions that still circulate in communities worldwide.

- Myth: “If I’ve had chickenpox, I’m immune to measles.”

The two illnesses are caused by completely different viruses. Chickenpox is caused by varicella‑zoster virus, while measles is caused by the measles virus (a paramyxovirus). Having recovered from one does not confer any protection against the other. - Myth: “The measles vaccine can cause autism.”

This claim was based on a retracted 1998 study that has been debunked countless times. Large‑scale epidemiological studies involving millions of children have repeatedly shown no link between the measles‑mumps‑rubella (MMR) vaccine and autism spectrum disorders. - Myth: “Adults don’t need the measles vaccine if they were vaccinated as children.”

Immunity can wane over time, especially if the initial series was incomplete or if the individual was never exposed to the wild virus. The CDC recommends a second dose of MMR for adults born after 1957 who lack documented immunity. - Myth: “Measles is just a rash and isn’t dangerous.”

While the characteristic red rash is a hallmark sign, measles can lead to severe complications such as pneumonia, encephalitis, and even death—particularly in malnourished children and immunocompromised individuals. - Myth: “Natural infection provides better immunity than vaccination.”

Both natural infection and two doses of the MMR vaccine confer lifelong immunity in most cases. However, acquiring immunity through infection carries a high risk of severe complications, whereas vaccination achieves protection safely.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Q: How long after vaccination does immunity develop?

Protective antibodies typically appear within two weeks after the first dose, but full immunity is achieved after the second dose, usually given 4–8 weeks later. - Q: Can I get measles from the vaccine?

No. The MMR vaccine contains live‑attenuated viruses that are weakened and cannot cause the disease in healthy individuals. - Q: What should I do if I’m exposed to measles?

If you have received two doses of MMR within the past five years, you are considered immune. If not, a single dose of MMR given within 72 hours of exposure can still prevent or lessen the disease. - Q: Is it safe for pregnant women to receive the MMR vaccine?

The vaccine is contraindicated during pregnancy. Women should receive the vaccine at least one month before conception or after delivery.

Clearing up these myths and answering common queries is essential for building public confidence in vaccination programs, reducing outbreaks, and protecting vulnerable populations from a disease that is both preventable and, in many cases, fatal.

Conclusion: Future Challenges and Prevention Strategies

Measles remains one of the most contagious viral diseases on the planet, and despite the remarkable success of vaccination programs, the world still faces significant hurdles in eradicating it completely. The next decade will be defined by how public health systems respond to emerging threats such as vaccine hesitancy, geopolitical instability, and the evolving landscape of viral genetics. Understanding these challenges is essential for shaping policies that protect the most vulnerable populations—infants, immunocompromised individuals, and communities with limited access to health care.

Key future challenges include:

- Vaccine hesitancy and misinformation: Social media platforms have amplified unfounded fears about vaccine safety, leading to pockets of under‑immunized communities where measles can rapidly spread.

- Disruption of routine immunization services: Conflict zones, natural disasters, and the lingering effects of the COVID‑19 pandemic have interrupted regular vaccination schedules, creating immunity gaps.

- Genetic drift of the virus: While the measles virus is relatively stable, minor mutations could affect diagnostic accuracy or vaccine effectiveness, underscoring the need for robust surveillance.

- Global travel and migration: Increased movement of people accelerates the cross‑border transmission of measles, demanding coordinated international response mechanisms.

To overcome these obstacles, a multi‑pronged prevention strategy is required:

- Strengthening routine immunization infrastructure: Invest in cold‑chain logistics, training of health workers, and community outreach to ensure every child receives two doses of the measles‑containing vaccine (MCV) by age 15 months.

- Targeted communication campaigns: Leverage trusted local voices and evidence‑based messaging to counteract myths and build confidence in vaccines.

- Enhanced surveillance and rapid response: Deploy real‑time reporting tools and mobile laboratories to detect outbreaks early and mobilize containment teams.

- International collaboration: Support global initiatives like the WHO’s Measles & Rubella Strategic Advisory Group to share data, resources, and best practices across borders.

- Research and development: Continue to refine vaccine formulations, explore thermostable options for low‑resource settings, and study the long‑term immunity conferred by newer combination vaccines.

In summary, the battle against measles is far from over. By anticipating future challenges and implementing comprehensive, evidence‑driven prevention strategies, the global community can move closer to the ultimate goal of measles elimination—and protect the health of generations to come.